Ruth Goodman is one of my favourite historians. I’ve watched several of her shows and have seen her as a guest on other history programs, and am always impressed by how she tries to live as period-authentic as she can during a project. I don’t have that much commitment to anything!

I’ve recently finished her book How to be a Victorian, which I was very excited about. If you’ve read this blog before you’ll know that my favourite part of history are the smaller, everyday moments of regular people – and that’s kind of Ruth’s whole thing. This quote from the book is a prime example of why I love her – when talking about dry rubbing instead of washing, she writes:

It works. I know, because I have tried it for extended periods. Your skin remains in good health and any body odour is kept at bay . . . The longest I have been without washing with water is four months – and nobody noticed.⠀

Here are some of my favourite facts and anecdotes from the book:

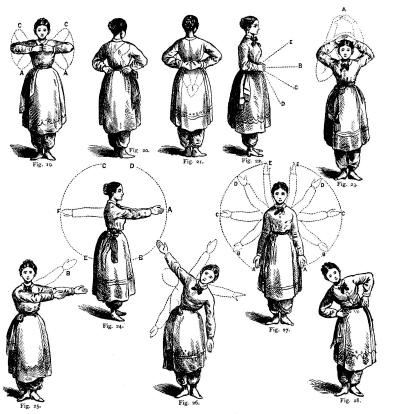

- On approved exercise for women (which focused mainly on the arms and chest, because they believed at the time that the female body – particularly the reproductive organs – was at risk of permanent damage if it was exerted too much): “My daughter and I have attempted calisthenics, with mixed results. I, personally, found the exercise to be ridiculously simple. Standing still in a room while waving my arms about did not feel at all taxing or exercising … My daughter, however … was complaining that her arms and shoulders ached, and the next day she was visibly stiff and sore.” I have to say, I’m with her daughter on this one! I tried the exercises too, and gave up after a couple of days. Goodman goes on to suggest that it could be due to our modern life of sitting over a computer keyboard or writing at a desk. If you’re curious, you can check out the Victorian calisthenics routine here. And if you’re curious about the sorts of exercises recommended just after the Victorian period, check out my entry on exercises for women from the 1910s!

- Newborns were no longer being swaddled, but they did wear a binder, a “simple strip of cloth that was wound around the ribcage and abdomen.” It helped the umbilical cord heal, and also catered to the belief that babies were born with soft bones. By the age of nine months, the binder was replaced with a stay band, described in the book as “a soft mini-corset,” using vertical rows of string for support instead of whalebone used in adult corsets (which also made them less tight than adult corsets).

- The monitor system was introduced to education, where students about 12-14 years old were taught lessons by the school’s master each day, and then in turn supervised the younger children while the whole class was taught. They were paid a bit of money for this, too.

- Unsavoury food additives were well-known, even if authorities didn’t do much to stop it. Each individual person was expected to look out for things like chalk and alum added to town milk. Some other common additions were brick dust used to thicken cocoa, and pipe clay in bread and flour.

- Sewing was such a major part of female life that needlework patterns aimed at young girls simply told them what stitches to use where, and gave an illustration of the finished product. No terms were explained, because girls were expected to know them.

You can find the book on amazon.ca and amazon.com – let me know if you read it!