One of the reasons I love reading Victorian/Regency novels is that I get a glimpse of the everyday rituals, strange to us now, that were so important to the people performing them. One of those rituals that always seemed at once charming and terrifying to me was the obligation of the morning call 0r social visit. So much seemed to hinge on those visits!

For example, from Jane Austen’s Persuasion:

“Where shall we go?” said [Mary], when they were ready. “I suppose you will not like to call at the Great House before they have been to see you?”

“I have not the smallest objection on that account,” replied Anne. “I should never think of standing on such ceremony with people I know so well as Mrs and the Miss Musgroves.”

“Oh! but they ought to call upon you as soon as possible. They ought to feel what is due to you as my sister . . .”

And then there was the first call paid to Margaret and Mrs Hale by Mrs Thornton and her daughter in Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South. Mrs Thornton’s son insisted that she pay this call, and she was not exactly thrilled about it:

As dinner-giving, and as criticising other people’s dinners, [Mrs Thornton] took satisfaction in it. But this going to make acquaintance with strangers was a very different thing. She was ill at ease, and looked more than usually stern and forbidding as she entered the Hales’ little drawing-room.

It ended up being a very tense visit for everyone involved, yet the Hales were still expected to pay a return call to Mrs Thornton.

Of course, obligations were obligations, at least to the people of certain social classes, and according to Daphne Dale, “the etiquette of visiting is not to be slighted.” Paying calls – whether visits of friendship, ceremony, condolence, or congratulation – was a way to initiate and continue valuable social connections and friendships. They helped make introductions between newcomers to a neighbourhood and the people in the social class they would be expected to know. They were also “a kind of safeguard against any acquaintances which are thought to be undesirable,” in the words of Lady Colin Campbell.

By 1922, “within the walls of society itself, the visit of formality [was] decreasing.” So it was odd for me to find a detailed section on visiting in my c.1938 edition of Mrs Beeton’s Household Management. Here are some of the highlights:

- Morning calls, despite the name, were made after luncheon, between 3 and 5pm.

- They were required “after dining at a friend’s house, or after a ball, picnic, or other party.”

- The visits were expected to last only about 15-20 minutes.

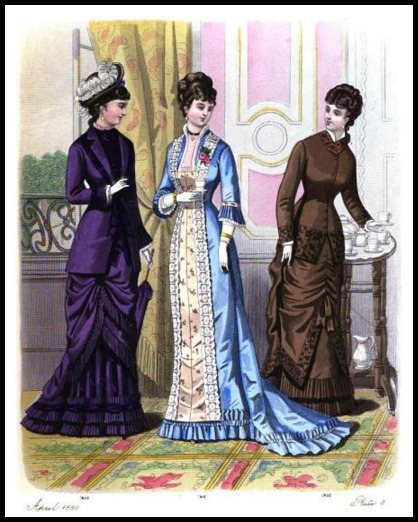

- Underdressing was preferable to overdressing.

- Pets were not allowed to accompany you on visits, especially if the person you’re visiting also had a dog, because “anything may happen!”

- “At Home” Days were special days set aside to receive visitors every week, fortnight, or month.

- If you received a call that interrupted you in the middle of light needlework, you could keep at it during the visit. All other tasks had to be put aside.

- Of course, it was on the visitor to gauge the situation and ensure they weren’t intruding on anything important such as a meal.

- People were encouraged to keep “accounts” of visits given and returned. As expected, this was to help determine whether or not to bother with future visits.

- Visiting cards with your name and address were left with a servant or in the front hall to act as an introduction, to note that a visit had been made to someone who was not at home, or to signify your condolences.

The rules for cards alone were . . . well, just read this:

In making a first call, if your acquaintance or friend be married, and her husband be alive, your own card and two of your husband’s should be left (your husband’s second card being intended for the husband of the lady visited). Should your acquaintance be unmarried, your own card and only one of your husband’s should be left, unless the father of brother of your friend be living in the same house; then another of your husband’s cards should be left for them.

There were also rules for when a lady stopped leaving two of her husband’s cards and started leaving only one, and what to do with your card if you’re in a “motor or carriage” (the servant will come to you and take it).

There was already so much etiquette in mind when paying the call itself – a lady can offer a gentleman her hand but doesn’t shake it, and she bows to unmarried men only – that I think keeping track of the visiting card rules would be my undoing. I would probably just fling cards down on a table and never be invited anywhere ever again!

References:

- Austen, Jane. Persuasion. 1818. (Available on amazon.ca and amazon.com)

- Gaskell, Elizabeth. North and South. 1855. (Available on amazon.ca and amazon.com)

- Dale, Daphne. Our social customs. A practical guide to deportment, easy manners, and social etiquette. Chicago: W.B. Conkey Company, 1895.

- Lady Colin Campbell. Etiquette of Good Society. London: Cassell and Company Limited, 1893.

- Emily Post. Etiquette in society, in business, in politics and at home. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1922.

- Daisy Eyebright. A Manual of Etiquette with Hints on Politeness and Good Breeding. Philadelphia: David McKay, 1873.

- Isabella Beeton. Mrs Beeton’s Household Management. London: Ward, Lock & Co. Limited, c.1938.