One of my favourite things about Filipino food is all of the outside influences made undeniably Filipino in their interpretation. I like to use Filipino food in my writing, and it’s become a key part of my mixed-race identity too.

The Philippines is made up of many different cultures and languages, and this isn’t meant as a definitive definition of Filipino cuisine. I just wanted to celebrate it. As a mixed-race person, it reminds me that “being Filipino” is fluid, a thread to weave through many contexts.

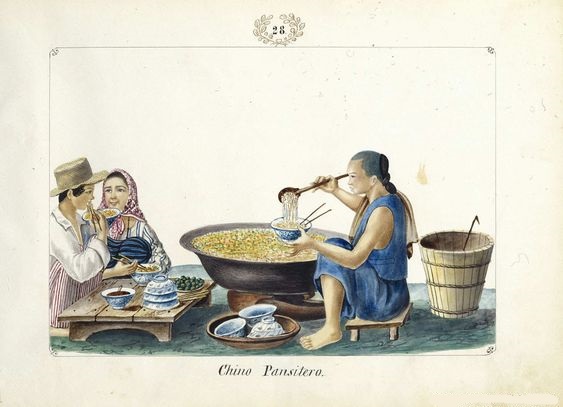

Chinese influences on Filipino food history

» Binondo, in Manila, is the world’s oldest Chinatown. Before Spanish colonization, migrants from Fujian and Guangdong came to the Philippines and gave us food like lumpia, siopao, and pancit. These dishes are often differentiated from the Chinese versions by their fillings or accompaniments: pork asado, smoked fish, vinegar-based dipping sauce.

The area of China that these influences came from is one reason Filipino food isn’t known for being spicy (there are exceptions, of course). Instead we love sour, and strong umami. My spiciness-aversion was something I had a hangup about until a friend made a lemon risotto that was deemed inedibly sour by everyone else, and I ate my portion as well as the others. It was delicious! Now, I see how Filipino my own palate actually is, and it makes me proud.

(Side note: In The Quiet is Loud, I specifically chose the Filipino-Chinese “Tanangco” as Freya’s surname.)

Indian influences on Filipino food history

» According to Felice Prudente-Sta. Maria, the karihan was a type of food stall influenced by sepoys, Indian infantrymen who revolted or deserted during the British invasion of Manila in the 1760s. They integrated into Filipino society and over the years began to sell curry (“kari” in Tagalog) dishes to travellers, improvising with local ingredients. This is one potential origin of kare-kare, my favourite Filipino dish. The word “karihan” was hispanicized to “carinderia,” a term still used today for a type of quick-service restaurant (also known as “turo-turo”).

(A turo-turo restaurant is featured in The Quiet is Loud, inspired by my sometimes disorienting relationship with them as a half-Filipino person.)

Another Indian influence: the classic Filipino condiment atchara was influenced by the Indian achar.

Spanish and American influences on Filipino food history

» And of course, we have the food influence from colonizer cultures: Spanish and American. It’s harder for me to be 100% thrilled about these influences, but I can’t deny that they’re there, and that we’ve made them our own. I also can’t deny that I love these foods too. Adobo is a precolonial dish with a colonial name. We have our own polvorón. We have our own empanadas. We have our own chicharon. Imagine Filipino cuisine without pandesal or Spam or Jollibee – I definitely can’t.

(In TQIL, having Freya and Javi bond over a good-natured chicharon vs chicharrón debate was important to me. I sometimes feel like I relate more to people who also come from Spanish-colonized cultures than I do to other Asians, partly for food reasons.)

NB: I’ve made every effort to find reliable historical sources for traditions that were often not recorded until much later, if at all. Please keep in mind that I’m not a professional historian, and I’m also limited by English-language sources and the foibles of Google Translate.

Main sources:

- “How Binondo Became the World’s Oldest Chinatown,” Justin Umali

- “Republic of Pansit,” Nancy Reyes Lumen

- “The Foods of Jose Rizal,” Felice Prudente Sta. Maria