In Finno-Ugric paganism, the bear’s true name was too sacred to speak aloud, lest you attract it. It was replaced with euphemistic, respectful names instead.

Finnish euphemisms for “bear”

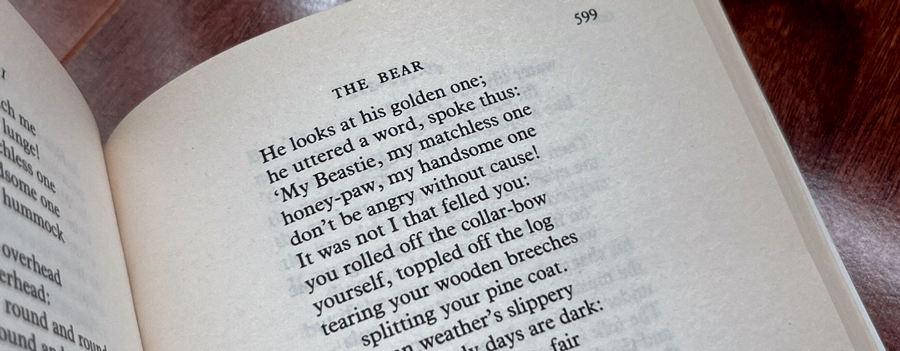

Because speaking the true name of the bear was taboo to ancient Finno-Ugric people, they used terms of endearment and euphemisms like mesikämmen (“honey-paw”,) metsän omena (“apple of the forest”,) and metsän kuningas (“king of the forest”). One common name for the bear in Finnish paganism was “Otso” (in fact, Otso is a Finnish male name today, and it’s even the name of the bear character in Finnish Duolingo). Even in the Kalevala, the post-Christianity 19th century collection of Finnish epic poetry, the bear is called by many names. Today, the modern Finnish word for bear, karhu, began as one of these sacred nicknames.

Otso’s mythical origins in Finnish paganism

Whatever the name people used, they weren’t necessarily referring to a singular bear. Instead, they were referring to the animistic spirit of all bears. Some say Otso came from the Ursa Major constellation, some say it was born when the sky god Ukko threw some wool into the water that washed up onshore, and some say it was born on the top of a pine tree. In the latter origin story, the belief was that the bear was created by the ancestor deity Hongotar (whose name came from “honka,” a pine tree).

Finnish pagan ritual of peijaiset: honouring the bear in death

When a bear had to be killed, many rituals of protection and honour took place. First, the hunters sang ritual songs to protect them when entering the liminal space of the forest, and to convince the bear’s spirit that the death was an accident (Väinämöinen does this in the Kalevala too). Then the sacred ritual of karhunpeijaiset was performed – peijaiset being a ritual memorial feast to honour a slain animal. After hunting a bear, this feast was held in Otso’s honour, and more songs were sung. According to Marianna P Ridderstad, peijaiset was “both the wedding and the funeral of the bear, who was addressed as kouko, the grandfather, and revered like a human ancestor or a bridegroom.” At the end of the feast, Otso’s bones were carefully buried at the base of a sacred pine tree and its skull was placed high in the tree so its spirit could return to the stars. Its teeth and claws may have been given to the hunters who killed it.

Through this cycle of ritual, the bear’s death was transformed into rebirth – a return to the cosmos from which it came, and an opportunity to return to the body of another bear in the future.

The bear spirit as ancestor to Finno-Ugric peoples

Some Finno-Ugric people, like people in many other northern cultures, believed the bear was the ancestor of us all. This sense of kinship deepened their reverence. The bear lived in a sacred liminal space, connecting people to the spiritual world through respect and ritual.

Even now, echoes of these beliefs remain in Finnish language, stories, and respect for the forest. The neopagan community Karhun Kansa (People of the Bear) retains the belief of bear-as-ancestor, and honours the spirit of Otso with seasonal rituals, reminding us that the bear is not forgotten.

Language, ritual, and the power of liminal space

With Finnish bear mythology, the importance of ritual language and the reverence for liminal space sticks with me. Ritual songs protected hunters in the liminal world of the forest (a place I love returning to in my novels and my life, though I have yet to write about a bear spirit). Language became ritual, and ritual became reality. The bear is a protected species in Finland today, and hunting is strictly controlled – and it’s Finland’s national animal too.

Interestingly, the Finnish language doesn’t have a word for “the.” I wonder if this helped encourage the feeling of familiarity with the sacred spirit of (the) Bear.

In my writing, I love playing with language and ritual in this way. The names my characters use for each other has power – and it complements the prevalence and power of nicknaming in Filipino culture as well.

Speaking of which, the sacred status of the bear in Finnish paganism has always amused me a little because my family nickname is Bear. It’s very much a pet name though, so only my parents and a few aunts and uncles ever use it. Growing up I didn’t want people knowing about the nickname at all, and even now I feel a little odd about admitting it on the public internet. While it was my Filipino dad who gave me that nickname for an entirely unrelated reason, I’ve always been curious what my Finnish family thought of it. And I’m sad that I never once used it to my advantage to win an argument.

Liked this post? Consider subscribing to my newsletter and get my free folklore guide:

“Boundary Keepers & Path Shifters.”

NB: I’ve made every effort to find reliable historical sources for traditions that were often not recorded until much later, if at all. Please keep in mind that I’m not a professional historian, and I’m also limited by English-language sources and the foibles of Google Translate.

Main sources:

https://helda.helsinki.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/ba73551f-3c12-46bc-bae2-3cbcdfc222d8/content

https://helda.helsinki.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/19485fd9-c2a6-4423-bb1d-80bc114cd4ae/content

https://scandification.com/finnish-mythology-creatures-and-finnish-folklore/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltic_Finnic_paganism#Sacred_animals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hongatar